Editor’s note: This article first appeared at The American Spectator.

“I’ll be home for Christmas, you can plan on me.”

So crooned Bing Crosby in December 1943. The song was a lament for countless boys fighting abroad in World War II, longing to be home for Christmas. By Christmas 1945, the wish became a plan — a reality. For the first time in several arduous years, our boys were home for Christmas.

One of them was Frank Kravetz. He had arrived stateside in New York City and hitchhiked all the way to Pittsburgh. He unceremoniously arrived at his folks’ front door — no dramatic music, no parade. He hugged his mom and dad and sat down. He found and married his sweetheart, Anne.

Frank was lucky to be alive, let alone home.

A tail-gunner in the Army Air Corps, on November 2, 1944, Frank was blown out of the sky in a bomb-run over Germany. He barely was able to parachute out of his B-17 that was filled with holes. He hit the ground and, by his description, “rolled like a shot up jack-rabbit.” He was immediately captured by German troops, who took Frank to what he called the “hell-hole” of a Nazi prison camp in Nuremberg, which he feared he would never leave alive, especially as his weight dwindled down to 125 pounds. He eventually was liberated and found his way home to smoky East Pittsburgh — home for Christmas 1945.

“Just existing became what was important,” Frank told me in May 2011. “I prayed throughout my ordeal, asking God for help.”

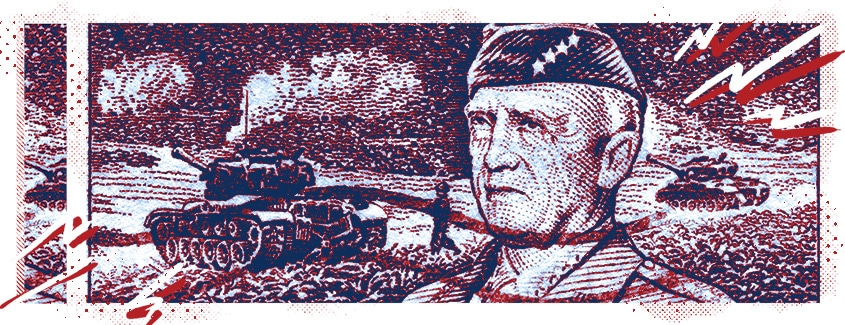

Frank owed his ticket out of prison to General George S. Patton. Frank’s liberation had come on April 29, 1945, courtesy of General Patton’s Third Army. “After the flag was raised,” recalled Frank, “General Patton rolled in, sitting high in a command car. His very presence was awe-inspiring. I stood there staring at General Patton, our liberator, appearing larger than life.” Thousands of emaciated, ecstatic POWs, overcome with emotion, chanted, “Patton! Patton! Patton!” Standing in the car, Patton seized a bullhorn and spoke: “Gentlemen — you’re now liberated and under Allied control…. We’re going to get you out of here.”

It finally hit Frank: “I’m going home. I’m really going home!”

Home for Christmas 1945, Frank was. But ironically, George Patton was not. The great general wouldn’t make it home for that Christmas. What happened to Patton stunned and saddened Americans that December 1945.

Patton died four days before Christmas, on December 21, 1945, as a result of injuries from a freak vehicle incident in Germany. He died not at the hands of German soldiers but at the hands of an American GI driving a truck down a German side street. He died not on the battlefield but on a roadway. He was only 60 years old. It was a complete shock. Patton had been an icon, a hero — as Frank Kravetz put it, a truly larger-than-life figure.

General Patton’s life and death are not forgotten this December 2020, thanks to filmmaker and author Robert Orlando, who has just released a fascinating new book, The Tragedy of Patton. The book follows a major film that Orlando did on the death of Patton, titled Silence Patton. The film explored what Orlando calls “the tragic notion that American politicians/leaders did not heed Patton’s caution and try to prevent a Cold War.” The book expands on this initial theme to consider if Patton, in light of his freakish accident and death, was able to achieve what Orlando refers to as his “God-felt destiny.” Orlando also regrets “our modern loss” of Patton’s “great legacy, of the brave men and women who fought or died in the war, and what generals and Cold War warriors like Patton represented.”

Orlando begins his book with that fateful moment in December 1945 when Patton’s post-war life took a turn no one expected:

It is December 9, 1945, seven months since the end of the war in Europe. On a war-torn, two-lane highway in Mannheim, Germany, the most formidable and audacious American commander of the Second World War, General George S. Patton, sustains life-threatening injuries when a 2.5-ton U.S. Army truck crushes his Cadillac Sedan on the eve of his departure for the United States. Patton, his nose broken, his scalp half-torn off, and his body paralyzed from the neck down, is rushed to the hospital in Heidelberg….

The radiator of the Cadillac was smashed, but not a single window of the big car was broken. The right front fender of the Sedan and the motor were pushed back, but no other part of the body had so much as a scratch. And though three persons were riding in the car, only one was hurt. Indeed, for Patton, the collision would prove to be lethal. It half-scalped him, broke his nose, and — most importantly — broke his neck, paralyzing him.

Patton was dazed but still conscious after the impact. “What a way to start a leave!” he joked. The other occupants of the crashed vehicle casually walked away. And yet, “Old Blood and Guts,” who envisioned for himself nothing short of a glorious battlefield death, was rushed to a German hospital. Paralysis set in. “If there’s any doubt in any of your Goddamn minds that I’m going to be paralyzed for the rest of my life, let’s cut out all this horse-shit right now and let me die,” Patton characteristically snapped.

The prognosis was bleak. Gen. Patton desperately clung to life. The decisive man in charge on the battlefield now took orders from nurses; he was under their command, fixed in place, confined to bed.

“As the hours slip by,” writes Orlando, “resignation sets in. Patton was like a drowning man who saw his whole life pass before his eyes.” The general said in disgust: “This is a hell of a way to die.”

Not many were permitted to see Patton in those final hard days as his lungs slowly filled with fluid. To the shock of the world, he succumbed early in the evening of December 21, dying in his sleep of pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure.

Orlando sums up: “The hospital staff can only do so much, and Patton dies on December 21 — an ironic end for a man who believed his destiny was to lead the world’s greatest army in the world’s greatest war, and even die as ‘the last man from the last bullet.’ ”

As many readers here know, there has long been controversy and conspiracy theory over Patton’s bizarre death. Robert Orlando does not dodge it. He jumps into the ongoing unsettled enigma of Patton’s not merely tragic but mysterious demise. It’s a topic he has studied for decades (long before the likes of Bill O’Reilly addressed it). Orlando is careful not to endorse conspiracy theories, but he also doesn’t shy from hitting them head on. Orlando writes:

But why is Patton the only one to sustain serious injury in the collision? To raise further suspicions, there is no autopsy. Thompson — the man driving the truck that struck Patton’s vehicle — and his two passengers are drunk, but no tests are conducted before they disappear. The official “accident” report and key witnesses cannot be located. No investigation takes place.

Was this a freak accident, or were more sinister forces at play? If so, who would want to kill America’s greatest general? Patton had vowed to “take the gag off” after the war and tell the intimate truth about controversial decisions and questionable politics that had cost the lives of his men. He threatened a war with the Russians and disobeyed orders by keeping a German army intact for that purpose…. Is it possible that his untimely death was the result of his refusal to be silent about the wrongdoings during the war?

I’ll leave those questions and details to Robert Orlando’s intriguing treatment of the tragedy of General Patton’s final days in December 1945.

But no matter what the truth about George S. Patton’s strange and shocking death, it’s easy for us today to be unaware of the odd context. His death had occurred, of all times, at Christmas 1945, as Americans celebrated peace for the first time in years. Christmas that year was a blessed moment of joy for the families and men of the war — that is, for those who made it home.

Gen. George Patton, however, did not make it. His death was a bittersweet moment that Christmas for all those boys who admired his leadership in winning the war.