In West Virginia v. EPA, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled by a 6-3 majority that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had exceeded its statutory authority by issuing regulations that would essentially dictate to power-generating utilities what fuel sources they must use. The EPA sought to force utilities to phase out fossil fuels and instead generate electricity from wind and solar technologies.

The Courts ruling is praiseworthy in at least two respects. First, it helps to restore the original constitutional order – specifically, the balance of power between the three branches of government. The Court ruled that only Congress, not unelected bureaucrats in the executive branch, could make such a far-reaching decision.

Secondly, the decision shines resplendently as a model of judicial consistency. In the recent Dobbs case, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on the grounds that the Court itself had usurped the legislative prerogative to write laws governing abortion. Just so, in West Virginia, the Court corrected another usurpation of the legislative prerogative – this one by the EPA. It is very encouraging for those who believe in the rule of law to see the Supreme Court take a clear stand that each branch of government must stay in its own lane and restrict itself to exercising only the powers and responsibilities assigned to its own branch.

Secondly, the decision shines resplendently as a model of judicial consistency. In the recent Dobbs case, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on the grounds that the Court itself had usurped the legislative prerogative to write laws governing abortion. Just so, in West Virginia, the Court corrected another usurpation of the legislative prerogative – this one by the EPA. It is very encouraging for those who believe in the rule of law to see the Supreme Court take a clear stand that each branch of government must stay in its own lane and restrict itself to exercising only the powers and responsibilities assigned to its own branch.

In contrast to the consistency shown by the majority in West Virginia, the official dissent written by liberal Associate Justice Elena Kagan was an example of confused, self-contradictory statements. Justice Kagan wrote, “Whatever else this Court may know about, it does not have a clue about how to address climate change…The Court appoints itself – instead of Congress or the expert agency – the decision maker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

In the first place, Kagan’s charge that the Court has named itself “the decision maker on climate policy” is completely counterfactual. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts explicitly stated, “A decision of such magnitude and consequence [i.e., mandating a new energy infrastructure for the country] rests with Congress itself, or an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from the representative body.”

Kagan’s misrepresentation of the majority’s opinion isn’t the only defect in her opinion. She states that the Supreme Court doesn’t have the knowledge or expertise to oversee climate change policy. This is undoubtedly true. Why, then, did she not acknowledge that the Supreme Court lacked the knowledge and expertise – and the constitutional authority – to impose personal opinions on when life begins and what abortion policy should be?

Another inconsistency in Kagan’s opinion is that she is willing to state that the Court “does not have a clue about how to address climate change” while citing with approval the Supreme Court’s 2007 ruling Massachusetts v. EPA. In that ruling, the Court directed the EPA to regulate CO2 as a pollutant. But if the Supreme Court lacks expertise in climate science, as Kagan maintains, then what business have they designating CO2 as a pollutant? It appears that Kagan approves of Supreme Court decisions that coincide with her personal beliefs about climate change. Thus, her judicial philosophy on the Supreme Court amounts to ruling in favor of her personal policy preferences rather than upholding a consistent judicial principle.

The Supreme Court would have been well justified to have overturned the highly problematic Massachusetts v. EPA ruling in the West Virginia case. As I wrote in this space 13 years ago, classifying CO2 as a pollutant opened a Pandora’s box of troublesome issues.

Here is a brief summary of some of the problems of treating CO2 as a pollutant:

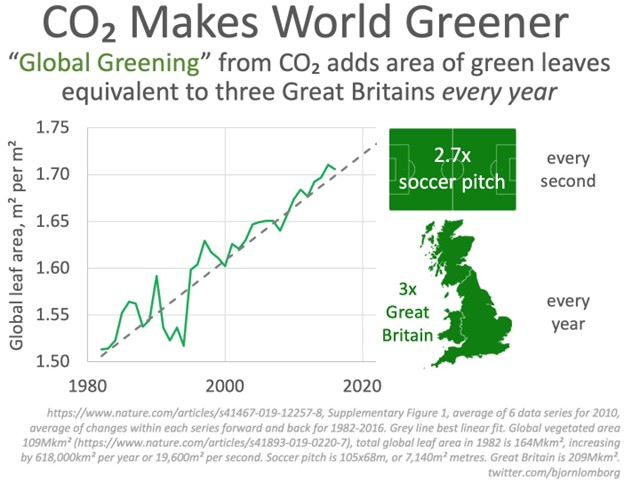

- The benefits of increased concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere are considerable. One study by a large group of scientists from around the world estimates that the CO2 enrichment of Earth’s atmosphere has resulted in the greening of a land mass equivalent to almost twice the size of the continental US. Another study quantifies the increased greening as equivalent to three Great Britains per year. NASA’s satellite-monitored vegetation index shows a global ten percent increase since the year 2000. A 2018 study found that the mother of all deserts – the vast Sahara – shrank by 700,000 square kilometers in the previous three decades, which is an area almost as large as Germany and France combined. Also, multiple studies have noted longer growing seasons and increased yields in the all-important agriculture industry.

- Because CO2 absorbs infrared radiation (“traps heat,” in everyday parlance) on a logarithmic scale, a doubling of the current atmospheric concentration would have a minimal temperature impact.

- It is inconsistent for EPA to regulate human emissions of CO2 and not regulate human-caused water vapor (think irrigation, fountains, artificial lagoons in Arizona subdivisions, etc.). Water vapor accounts for by far the dominant share of the greenhouse effect.

- Although Earth (thankfully) has warmed a couple of degrees since the end of the Little Ice Age in the mid-1800s, the atmosphere is just now approaching the temperatures of the Medieval Warm Period, which itself is a degree cooler than the Roman Period, which in turn is 1.5 degrees cooler than the Minoan Period almost 4000 years ago. And since factors such as variations in solar activity and cloud cover can alter Earth’s climate regardless of the greenhouse effect, the current obsession over CO2 is puzzling.

As I wrote 13 years ago, the way to put an end to the costly attempts by green ideologues to regulate CO2 is for Congress to pass a simple law: “For purposes of federal law, CO2 is not considered a pollutant.” The Supreme Court’s decision in West Virginia v. EPA has brought this issue to the fore. Consistent with the current Court majority’s belief that major policy decisions that affect our lives should be voted on by Congress, the Court refrained from overturning Massachusetts v. EPA and has deferred to Congress. Now Congress should act.