My father was a Presbyterian minister in rural northwest Alabama from 1961 to 1965. I came of age there, then left the University of Alabama with an M.A. in history in 1969. Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and Governor George C. Wallace framed the historical context of a changing south to which I returned in 2008.

In retrospect, 1963 was a watershed year in my life. On June 11, 1963, I watched on the television in our den as Governor Wallace stood in the door at the University of Alabama’s Foster Auditorium to fulfill a campaign promise to physically stop school desegregation. Quixotic as this proved, given that two African American students were already registered, the gesture got him re-elected three times. Later that summer, on August 28, I watched as Martin Luther King eloquently prophesized “one day right there in Alabama” black children would “be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” Eventually, those days arrived.

A month later, on Sunday, September 15, 1963, while I was in my room studying Spanish at the start of my high school senior year, my dad summoned me to the den where he had been watching professional football. A news bulletin revealed four young African American girls were killed at Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church when a bomb detonated under the backstairs by a women’s bathroom where they primped after Sunday School.

My dad, who previously had supported racial segregation, wept. “Son, if this is ‘defending our southern way of life,’ it’s not worth it.” The next Sunday his sermon was titled, “God the Father Implies the Brotherhood of Mankind.” It was not well received. Dad’s epiphany resulted in a series of sermons related to securing civil rights while abjuring violence in the process. On a January night in 1965, during my freshman year in Tuscaloosa, while dad was in Huntsville, Klansmen burned a cross on our lawn. This terrified my deaf-since-birth mother. They also shot and killed my dog. In April, my parents moved to serve a church in Coral Gables, Florida. I remained at the University of Alabama for four more years. My father’s ministry ended two decades later as a missionary in the Cayman Islands.

The bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, along with many other atrocities, were part of the warp and woof of life in Alabama during the turbulent 1960s. While a student, I heard Governor Wallace speak on campus every year at the annual Governor’s Day celebration. In 1967, his wife, the newly elected Gov. Lurleen B. Wallace, awarded me the Air Force ROTC’s “Military Excellence” medal. After I saluted her, Alabama’s real “Guvnor” standing beside her, heartily shook my hand, “Congratulations, son! Alabama is proud of you.” I nodded and smiled.

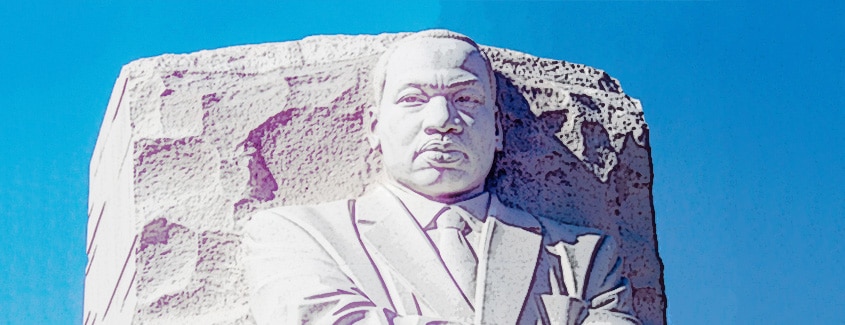

Martin Luther King, Jr. masterfully used rhetoric to deliver a powerful message that he effectively coupled to imageries of repression that included fire hoses, police batons, and cattle prods against demonstrators. The arc of history moved inexorably toward justice overcoming prejudice backed by Klan violence.

Change came slowly, subtly, but surely. On Monday, July 6, 1964, four days after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, my father, mother, and I drove to Tuscaloosa from Leighton, Alabama. A scholarship for which I’d applied required a family interview with one of the university’s deans. On the way into town dad spotted a Morrisons Cafeteria at campus edge. After the interview, dad suggested we have lunch there before the long drive home.

As we drove into the parking lot, we spotted Klan picketers in full regalia mulling around the entrance. Mom strongly urged going elsewhere. Dad grumbled, “Bozos don’t tell me where I can eat.” Those Klansmen intended to intimidate would-be patrons of any color.

As we approached, I noticed a sign, “You might be eating off the same plates as coloreds.” Undaunted, dad led us into the line where a hulking Klansman stepped in front of my father and snickered, “Y’all must be some kind of n—-r lovers.” Dad, a former collegiate football lineman, fixed that Klansman with a cold, unblinking stare and then replied in a measured and unwavering voice, “You bet.” The Klansman grunted, then stepped back. My father had become part of a changing south.

With time, many white southern hearts changed. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s message of peaceful resistance moved America toward his vision, stated eloquently on August 28, 1963: “A day will come when all God’s children … will be able to join hands and sing the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.’”

Today, we honor Dr. King’s memory.