Today marks the 40th anniversary of the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty. Historians consider the Egyptian-Israeli peace brokered by President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s to be the most important and impressive diplomatic achievement of an administration otherwise plagued by foreign crises. The “peace process” between those two erstwhile enemies ended decades of active animosity and conflict between them, and powerfully influenced the subsequent history of the Middle East and the world.

Since its creation by the United Nations in 1948, the modern Israeli state had clashed with its Arab neighbors and the Palestinian Arabs living within its borders. This antipathy stemmed from the Arab states’ rejection of the idea that the Jewish people had any right to a state in the Palestinian homeland. Moderate Arabs held that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory violated the terms of the UN General Assembly Resolution 181, which provided for the creation of separate Jewish and (Arab) Palestinian states.

Several wars and major international crises between 1948 and 1973 firmly established the Arab-Israeli conflict as the pivot on which Middle Eastern politics turned. It also served as a focal point in the global competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. In the wake of the Yom Kippur War (October 6–25, 1973), Secretary of State Henry Kissinger engaged in “shuttle diplomacy” to prevent future conflicts, resulting in the Egyptian-Israeli Sinai Interim Agreement (September 1975), also known as Sinai II. This established the principle of relying upon diplomacy as the first means to resolve conflicts between Egypt and Israel. It also resulted in stronger ties between Egypt and the West, but hurt Egypt’s relations with other Arab states.

President Jimmy Carter entered office on January 20, 1977. During his campaign, Carter—a committed Southern Baptist—had announced his intention to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict through a comprehensive peace settlement. Contacts with the Israelis and the principal Arab states (especially Syria, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia) seemed to indicate Arab interest in reconvening the Geneva Conference, which had met in 1973 in an abortive attempt to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict. In an attempt to reconvene the conference, the USSR and the United States issued the Joint US-Soviet Statement on the Middle East (October 1, 1977), but domestic backlash in the United States forced the Carter administration to back down from this proposal.

November 20, 1977 marked the beginning of the path to peace between Israel and Egypt, as Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat addressed the Israeli Knesset in Jerusalem. By flying to Israel, addressing the Knesset, and inviting them “to struggle for peace” with him, Sadat violated all of the notorious “Three No’s” set forth in the Arab League’s Khartoum Resolution of 1967: “no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with it.”

Sadat’s trip forced the United States to abandon its position, now acting as the sole mediator in bilateral Egyptian-Israeli negotiations, rather than serving as co-mediator (with the Soviet Union) in multilateral discussions between Israel and the Arab states. The Carter administration hoped to use the Egyptian-Israeli rapprochement as the framework for a comprehensive peace in the Middle East. As it happened, future efforts for a comprehensive peace failed.

Although some supported the peace process, most of Egypt’s fellow Arab states swiftly expressed their disapproval. In response to Sadat’s actions, the Arab League held a Summit Conference in Tripoli, Libya (December 2‒5, 1977). On December 4, Libya, Algeria, the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (i.e. South Yemen), Syria, and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) formed the Steadfastness and Confrontation Front, whose sole purpose was “to oppose all capitulationist solutions planned by imperialism, Zionism and their Arab tools.” The Front, enthusiastically supported by the Soviet Union, ultimately became little more than a surrogate for Soviet influence in the region.

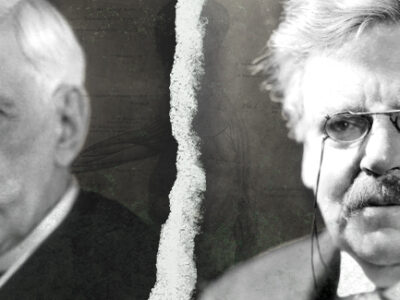

The year following Sadat’s Knesset speech proved difficult for Israel, Egypt, and the United States, as President Carter sought to broker a lasting and viable peace between the two Middle Eastern states. One of the greatest challenges to Carter’s personal diplomacy was the markedly different personalities of Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin; while Sadat was relatively flexible and open to most compromises, Begin was inflexible and intractable, demanding concessions which Sadat could not possibly make. This was a source of great frustration for the negotiators, and especially for President Carter.

When bilateral talks between the Egyptians and the Israelis were on the rocks in 1978, Carter took the initiative and invited Begin, Sadat, and their delegations to meet for intensive discussions at the president’s personal retreat at Camp David. Both sides accepted, and the three parties met September 5–17. Carter took great care to keep the media away from the site of negotiations, and tightly controlled the flow of information to and (especially) from Camp David, thereby giving the participants the seclusion needed to iron out a deal.

Sadat and Begin hated one another, however, and spent as little time together at Camp David as possible. This made negotiations incredibly difficult, forcing Carter and his advisors to engage in a miniaturized version of shuttle diplomacy during the discussions, taking messages from a delegation in one cabin to the other delegation in another.

After 13 days of tense negotiations, during which Sadat actually threatened to leave, all sides agreed to the Camp David Accords. The Accords consisted of two separate (but related) agreements. The first, “A Framework for Peace in the Middle East,” provided for the creation of a Palestinian state and the withdrawal of Israeli occupying forces from the West Bank. Second, “A Framework for Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel” outlined the terms of what later became the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty. Conditions of this framework provided for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Sinai Peninsula, the normalization of diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel, and the safe passage of Israeli vessels through the Suez Canal and the Straits of Tiran. In theory, the Accords would serve as the basis for the comprehensive settlement of the Arab-Israeli Conflict as a whole.

Six months later, on March 26, 1979, Sadat, Begin, and Carter signed the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty. In addition to the terms outlined in the second agreement discussed above, the treaty provided for both Egypt and Israel to receive billions of U.S. dollars in military and economic subsidies from the United States.

The Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty had a number of significant effects. Most obviously, it ended the conflict between Egypt and Israel. Although it did not end the broader Arab-Israeli Conflict, it did lay the foundation for future agreements within that struggle. Additionally, it completed Egypt’s shift from the Soviet camp to the Western and shored up the already-strong Israeli-American relationship.

Begin and Sadat won the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize because of the Camp David Accords. Carter had to wait to receive that honor in 2002, in recognition of his various humanitarian and diplomatic endeavors over the years. The treaty also had several unintended consequences, including the rise of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq as a regional power, and the general strategic shift away from the Arab-Israeli Conflict toward the Persian Gulf region.

Ultimately, however, the treaty was a remarkable accomplishment by any measure. Though it did not prevent future ground wars in the Middle East, it demonstrated the potential of personal diplomacy.

Most importantly, the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty showed that even the bitterest of enemies can put their differences aside for the greater good, but only if they are willing to put forth the effort.