Tonight, President Donald Trump will visit Minneapolis. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey stated, “While there is no legal mechanism to prevent the president from visiting, his message of hatred will never be welcome in Minneapolis.” For those too young to remember, the United States in 1963 was divided deeply over the growing civil rights movement—a division that later widened with the war in Vietnam.

In May 1963, I was a 17-year-old high school junior in Sheffield, Alabama. On May 18, I arrived at the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) pavilion in nearby Muscle Shoals three hours before President John F. Kennedy spoke commemorating the 30th anniversary of the founding of TVA. I huddled with my high school classmates on the front row to await the president’s arrival.

Shortly after noon, Governor George Wallace accompanied Kennedy onto the platform where local dignitaries, along with Senators Lister Hill and John Sparkman, stood respectfully. My classmates and I cheered and waved. I recall my amazement that JFK’s hair was a very light reddish brown—black and white TV missed those subtleties. The president turned his back to the gleeful crowd as he individually greeted the distinguished guests on the platform. Each time the president shook hands, Governor Wallace, standing behind him and facing the crowd, raised both arms with fingers raised in a “V.” The crowd roared its approval.

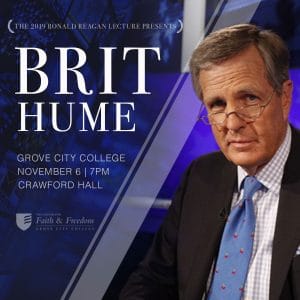

Join us on November 6, 2019 with senior political analyst for FOX News, Brit Hume. Grove City College President Hon. Paul J. McNulty ’80 and IFF Senior Fellow Dr. Paul Kengor will interview Brit for our 13th Annual Ronald Reagan Lecture. Admission is FREE but you must RSVP. Click to learn more.

Other subtleties were at work.

In just 24 days, on June 11, 1963, the University of Alabama would become the last major state university to drop its racial barriers. Most of the crowd greeting President Kennedy steadfastly supported Governor Wallace in his vow to block federally mandated desegregation by physically standing in the door of Foster Auditorium to prevent students Vivian J. Malone and James A. Hood from registering. The governor also had dubbed President Kennedy a “military dictator.”

My classmates and I were thrilled to see our president. Six months and four days later, on Friday afternoon November 22, we listened on the school intercom when Walter Cronkite’s cracking voice announced, “President Kennedy died at 1:00 PM Central Standard Time, some 38-minutes ago.” Everyone in my speech class wept.

As a major confrontation over desegregating the state’s flagship university loomed, on May 24, 1963 University of Alabama President Frank A. Rose and Vice President Jefferson Bennett flew to Washington to meet privately with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. The next morning, during breakfast at Robert Kennedy’s Hickory Hills estate in suburban McLean, Jeff Bennett told Robert Kennedy that Wallace planned to call out the Alabama National Guard. Kennedy reacted with alarm, but Rose assured him this was not to oppose desegregation. Wallace was also mobilizing the state troopers and sheriff’s deputies to keep the peace on campus. Bennett also warned that bringing in Army troops from nearby Ft. Benning might exacerbate the situation. President Rose suggested it would be better if President Kennedy federalized the still all-white Alabama National Guard. The attorney general quipped, “Let’s go see Jack.” The trio left for the White House.

An hour later, in the Oval Office, Frank Rose ran the suggestion by President Kennedy. Fearing a repeat of riots like those at the University of Mississippi in October 1962, President Kennedy suggested postponing Alabama’s desegregation until January 1965. Rose assured Kennedy there would be no riots and that Wallace also was committed to a peaceful resolution. President Kennedy turned to his brother, “Bobby, what do you think?” There was no hesitation, “Jack, if Frank says ‘no riots’ you can take it to the bank.”

On Tuesday, June 11, 1963, Governor Wallace, fulfilling a campaign promise, stood defiantly in the door of Foster Auditorium symbolically blocking desegregation. That afternoon, the already registered students returned supported by the federalized Alabama National Guard to symbolically “open the schoolhouse door.” Governor Wallace stepped aside vowing to “carry on the fight” in the courts.

On May 18 and June 11, 1963, issues were real and the country cleaved along political and racial lines. Just after midnight, following Wallace’s schoolhouse door stand, civil rights leader Medgar Evers was gunned down 185 miles away in Jackson, Mississippi. Nevertheless, on May 18, 1963, despite political disagreements, Alabamans treated their president with grace and civility. That spirit of unity and grace contributed to making for a peaceful desegregation of a campus located only one mile from Ku Klux Klan imperial headquarters in downtown Tuscaloosa.

We could use more of that civility today.