The McNulty Memo (Monthly Musings on Faith and Public Life)

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles looking at Christian faith in the public square. This is part of the Institute’s Center for Faith & Public Life initiative.

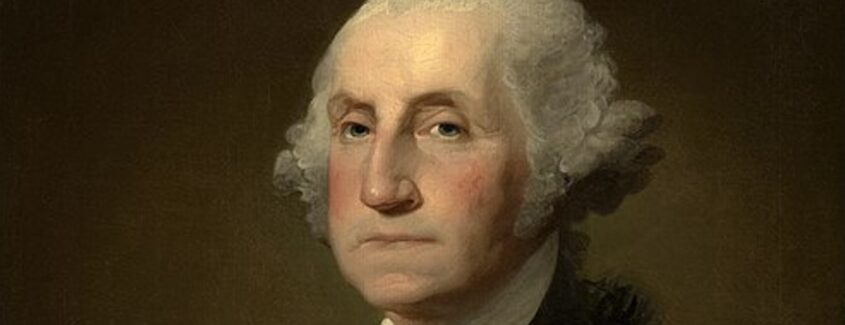

The official name for Presidents’ Day is “Washington’s Birthday,” and this year we have an entire week between the day of celebration, February 16, and Washington’s actual birthday of February 22. This offers us some extra time to remember America’s greatest statesman and the prominence he gave to genuine religious faith in our public life.

Many have undertaken the challenge of defining George Washington’s religious beliefs. An excellent addition to this body of work can be found in a book by my colleague Gary Scott Smith titled Faith and the Presidency. Dr. Smith thoroughly examines the available evidence of our first president’s faith. Warning readers about the complexity of this subject, he writes, “Some authors have portrayed the Virginian as the epitome of piety, and others have depicted him as the patron saint of skepticism.” Putting this question to the side momentarily, Dr. Smith emphasizes, “One point, however, is not debatable: Washington strongly believed that Providence played a major role in creating and sustaining the United States. In public pronouncements as commander in chief and president, he repeatedly thanked God for directing and protecting Americans in their struggle to obtain independence and create a successful republic.”

It is also clear that in his first and last addresses to his beloved nation, the father of our country affirmed the relationship between faith and our civil society. Washington’s unmistakable recognition of God’s immanence in the life of the new nation is a strong encouragement for believers advocating Christian values in the public square. Politicians don’t need to leave their faith on the steps of the capital building. George Washington didn’t.

On April 30, 1789, President Washington delivered the first inaugural address. It was the opening statement of the man most responsible for the new nation’s existence. He clearly felt the weight of his calling. Referring to the receipt of the news of his election 16 days earlier, he claimed that “no event could have filled me with greater anxieties.” He was “overwhelm[ed] with despondence” when he considered his “inferior endowments from nature” and lack of experience “in the duties of civil administration.” He even expressed concerns about his health.

I find it enormously impactful that arguably our two greatest presidents, Washington and Lincoln, were both humble men.

This remarkable humility was a source of Washington’s strength because it appeared to fortify his faith and direct his attention to the goodness of God in his life and the life of the new nation. Immediately following the disclosure of his reticence about his new calling, he professed in the florid prose of that time:

Such being the impressions under which I have, in obedience to the public summons, repaired to the present station, it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a Government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes, and may enable every instrument employed in its administration to execute with success the functions allotted to His charge.

These are not the words of a deist, as some have improperly labeled Washington, who sees God as the creator but one who is also far removed from the ongoing affairs of men. Rather, our first president called upon God’s blessing to “consecrate” (set apart) the government for sustaining the peoples’ liberties and happiness and enable it to fulfill its responsibilities. In other words, he believed that the government of the new country was dependent on God’s benevolence for its success.

Moreover, so widespread was Americans’ trust in God’s sovereign plan that Washington could observe with confidence that the members of Congress, his immediate audience, and the general public undoubtedly agreed with him. They were all eyewitnesses to God’s goodness and were therefore duty-bound to adore God and recognize His providence:

In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States.

Washington continued to express these convictions many times during his eight years in office.

In his “Farewell Address to the People of the United States,” first published on September 19, 1796, President Washington observed that religion and morality are “indispensable supports” to political prosperity. He described them as “the firmest props of the duties of Men and Citizens,” and added, “And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

After this address, a group of two dozen Philadelphia area pastors acknowledged “the countenance (support) you have uniformly given to [God’s] holy religion.” This proclamation followed Washington’s final words in office.

Thus, from his first words to his last, George Washington affirmed the place of faith in public life. He cherished religious liberty and respected the diversity of beliefs. But the man eulogized by Henry Lee as being “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen,” reminds us today that God’s providence is responsible for America’s freedom and prosperity and its citizens should continue to look to Him in gratitude and as the eternal source of lasting truth.